The Madison Symmetric Torus: A

Stepping Stone in the Quest for Clean Fusion Energy

John Sarff, Clint Sprott, and Grok Four

February 3, 2026

Imagine capturing the power of the sun in a machine on Earth. That's

the dream of nuclear fusion: smashing together light atoms, like

hydrogen, to release massive amounts of energy without the

long-lasting radioactive waste of traditional nuclear power. For

decades, scientists have chased controlled nuclear fusion—a way to

make this process happen steadily and safely in a reactor, producing

electricity for the world. It's a grand quest, full of challenges

like containing super-hot gases hotter than the sun's core without

them escaping or cooling down. Devices around the globe are testing

ways to do this, and one intriguing player is the Madison

Symmetric Torus (MST) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

This essay explores what the MST is, how it works in simple terms,

its key contributions, and why it matters in the broader push for

fusion energy.

First, let's set the stage with fusion basics. Fusion happens

naturally in stars, where gravity squeezes atoms together. On Earth,

we lack that gravity, so we use magnetic fields to trap and squeeze

a superheated gas called plasma—think of it as a soup of charged

particles buzzing around at millions of degrees. The goal is to get

these particles colliding enough to fuse, releasing energy we can

harvest as heat to generate electricity. But plasma is tricky; it's

like trying to hold a wisp of smoke with invisible hands—it wants to

expand, cool, or become unstable. Most fusion research focuses on a

design called a tokamak,

a donut-shaped machine that uses strong magnetic fields to keep the

plasma in a twisting path. Big international projects like ITER in France are betting on

tokamaks to prove fusion can work at scale.

But tokamaks aren't the only game in town. Scientists explore

alternatives because no single design might solve all problems, like

cost, efficiency, or stability. Enter the reversed-field pinch

(RFP), a cousin to the tokamak but with a twist—literally. In an

RFP, the magnetic fields are arranged so that the field lines

reverse direction near the plasma's edge, creating a more relaxed,

natural state for the plasma. This could make RFPs simpler and

cheaper to build, as they might need weaker external magnets and

handle higher power densities.

The MST is one of the world's leading RFP devices, helping us

understand if this approach could lead to practical fusion power.

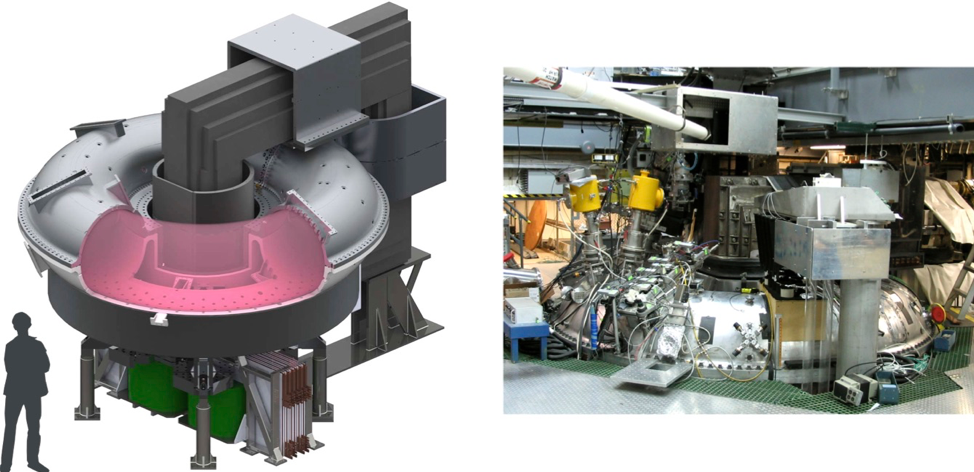

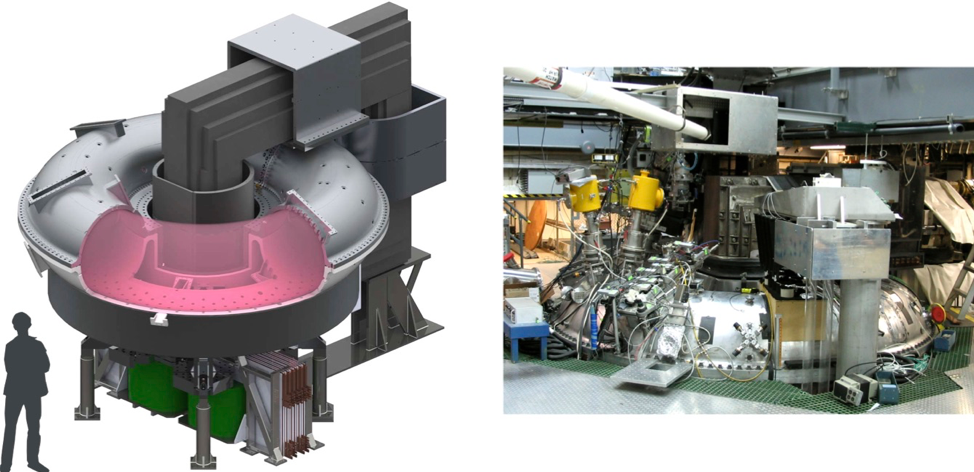

Built in the late 1980s after three years of construction, the MST

first lit up its plasma in 1988. It's housed in Thomas C. Chamberlin

Hall at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, part of the Wisconsin Plasma Physics Laboratory.

Picture a large metal donut about 5 feet across in the middle

(that's the "minor radius" of 0.52 meters) and 10 feet wide overall

(major radius of 1.5 meters). It's not huge compared to giants like

ITER, but its size makes it perfect for experiments—affordable to

run and tweak. The MST can crank up plasma currents to 600,000

amperes (that's a lot of electricity flowing through the gas) and

heat it to over 10 million degrees Fahrenheit, mimicking star-like

conditions on a lab scale.

How does it work? At its core, the MST uses electricity to create

magnetic fields that corral the plasma. A puff of gas is introduced,

which the electric field converts into a plasma in a spark-like

process, and then it drives a huge current through it--like turning

the plasma itself into a wire that generates its own magnet field.

In a standard tokamak, the main magnetic field runs strongly around

the donut's long way (toroidal direction), with a weaker field

looping the short way (poloidal). But in the MST's RFP setup, the

poloidal field is stronger, and the toroidal one flips direction at

the edge. This "reversal" lets the plasma settle into a stable,

low-energy state naturally, kind of like how a twisted rubber band

unwinds to relax.

It's different from tokamaks, where the plasma is kept farther from

the walls and relies more on external magnets. In the MST, the

plasma hugs closer to the chamber, which brings challenges like

dealing with turbulence but also opportunities for better

efficiency.The MST isn't just a static machine; it's a hub for

clever experiments that push fusion science forward. For instance,

researchers use "pulsed poloidal current drive" to send quick

electrical pulses that smooth out the plasma's current, reducing

wobbles and improving how long the heat stays trapped—key for

sustained fusion.

Advanced tools like lasers and ion beams probe the plasma's

temperature, density, and fields in real-time, giving scientists a

window into its chaotic inner world. One standout achievement came

in 2024: the MST team ran stable plasma at densities ten times

higher than the "Greenwald limit," a benchmark from tokamak research

that predicts when plasma gets too dense and goes haywire from

turbulence.

In simple terms, the Greenwald limit is like a speed limit for how

packed you can make the plasma particles before they start bumping

too wildly and losing energy. By carefully controlling voltage and

gas input, the MST smashed through this barrier without instability.

While the MST operates at lower fields and temperatures than big

reactors, this shows RFPs might handle denser plasmas better,

boosting fusion rates since more particles mean more collisions and

energy output.

Other wins include better confinement during experiments, detailed

maps of plasma turbulence, and insights into how magnetic fields

"relax" naturally—ideas that could apply beyond RFPs. So, where does

the MST fit in the fusion quest? Fusion research is like a puzzle

with many pieces: tokamaks lead the pack for now, but they face

hurdles like massive costs and disruptions (sudden plasma

collapses). RFPs like the MST offer a complementary path,

potentially leading to more compact, affordable reactors with higher

power output per size.

By studying turbulence, current drive, and high-density stability,

the MST provides data that could improve all magnetic confinement

devices, including tokamaks. It's also a bridge to astrophysics,

modeling how plasmas behave in space, like in solar flares or

distant galaxies. Funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, it's part

of a diverse U.S. fusion program that includes other concepts,

ensuring we don't put all our eggs in one basket.

In the end, the MST reminds us that fusion's holy grail—unlimited

clean energy—will likely come from teamwork across designs. While

ITER aims for breakthroughs in the 2030s, smaller innovators like

the MST refine the science today, inching us closer to a

fusion-powered future. As we face climate challenges, devices like

this keep the spark of hope alive, showing that with ingenuity, we

might one day bring stars to Earth.