Adventures of Two Young Hams

Quent Cassen (W6RI) and Clint Sprott (W9AV)

The year was 1955. Dwight Eisenhower was president, and it was a

much simpler time, especially in Memphis, Tennessee where

12-year-old Clint Sprott, ex-KN4BOM, had just received his Novice

Amateur Radio license in the mail. Two years earlier, 11-year-old

Quent Cassen, ex-WN4YMG, had also become a Novice. Within the year

we had upgraded to Generals and became lifelong friends, sometimes

called the “CQ twins” by local hams during our teenage years.

Our early Amateur Radio days were spent on 40

meters with low-power homebrew CW transmitters. Hams built a lot

of their own equipment in those days, especially teenagers on

weekly allowances. Clint mowed lawns, and Quent had a paper route

to make enough money to buy the parts to assemble their early

equipment. Quent had a Hallicrafters S-40B receiver, purchased

from Sears, and Clint used a National NC-98 receiver that Santa

Claus had left under the tree. Clint remembers the trepidation

with which he made his first QSO on 17 January 1955 with K4ASL,

nearly a mile away, on the 40-meter CW Novice band. Quent

remembers yelling to his mom “What should I tell him?” when it was

his turn to transmit.

Amateur Radio in the 1950s was quite different from today. There

was the thrill of listening to the first satellite to orbit the

Earth, Sputnik 1, launched by Russia in October 1957. Sputnik was

easy to tune in (click here

to hear what it sounded like) since it transmitted at 20.007 MHz,

just above WWV. Receivers weren’t so good in those days, and it

helped to have WWV as a marker to find the right frequency.

Probably the Russians did that on purpose lest we fail to notice.

Propagation was so good in 1957 that we could hear Sputnik much of

the way around the Earth during some passes. Sometimes we could go

outdoors and see the satellite pass overhead just after dusk.

There was a 1 kHz Doppler shift on the Sputnik signal as it

passed, but the receivers that teenagers could afford weren’t

stable enough to notice it.

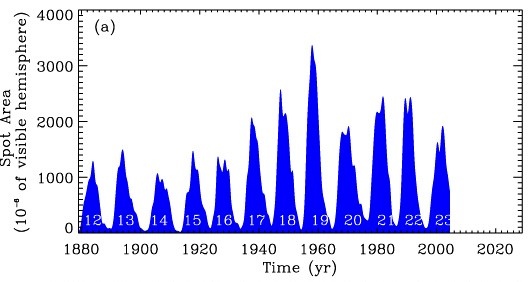

We were surprised how easy it

was to work DX with very modest equipment. Ten-meter CW was really

hot. On the weekends we would get up early and work one European

station after another, staying with it all day until stations from

Australia and Japan would start to come in just before 10 meters

went dead in the evening. The world seemed a very big place to two

kids who hadn’t ventured very far from home. What we didn’t know

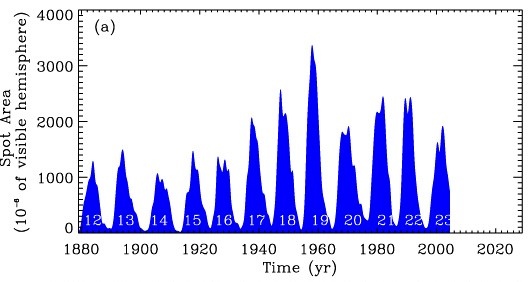

was that sunspot cycle 19, which peaked in 1957, still stands as

the all-time record. DX contests were a thrill for us. By 1959, we

both had our DXCC certificates and many other operating awards.

We were surprised how easy it

was to work DX with very modest equipment. Ten-meter CW was really

hot. On the weekends we would get up early and work one European

station after another, staying with it all day until stations from

Australia and Japan would start to come in just before 10 meters

went dead in the evening. The world seemed a very big place to two

kids who hadn’t ventured very far from home. What we didn’t know

was that sunspot cycle 19, which peaked in 1957, still stands as

the all-time record. DX contests were a thrill for us. By 1959, we

both had our DXCC certificates and many other operating awards.

Before we were old enough to drive, we converted a Heathkit

11-meter Citizens’ Band transceiver to 10 meters and mounted it on

Quent’s bicycle. The equipment was all vacuum tubes, and so we had

to convert the output of a small wet cell battery to high voltage

DC to power the tubes. The bicycle had an 8-foot whip antenna on

the back, constructed from an old fishing pole. It was fun working

locals as well as DX on 10 meters AM with only 5 watts while

pedaling down the street. Everyone thought we were crazy. Why

would anyone want their own personal communicator to take with

them in their vehicle??

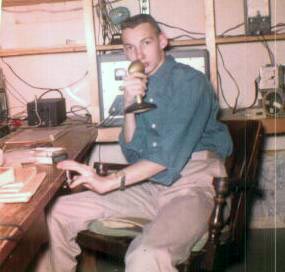

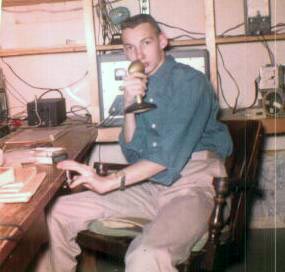

While still in high school we each

built our own Heathkit DX-100 transmitter. This photo is of Clint

in his basement shack, in front of his DX-100. We built many other

pieces of Heath equipment – receivers, transmitters, and test

equipment. Allied Radio in Chicago (via mail order) and the local

Amateur Radio emporiums in Memphis (Bluff City and W&W) soaked

up a lot of our allowances. We occasionally used the popular World

War II ARC-5 Command Set equipment that was readily available and

easily adapted for use on the Amateur Radio bands.

While still in high school we each

built our own Heathkit DX-100 transmitter. This photo is of Clint

in his basement shack, in front of his DX-100. We built many other

pieces of Heath equipment – receivers, transmitters, and test

equipment. Allied Radio in Chicago (via mail order) and the local

Amateur Radio emporiums in Memphis (Bluff City and W&W) soaked

up a lot of our allowances. We occasionally used the popular World

War II ARC-5 Command Set equipment that was readily available and

easily adapted for use on the Amateur Radio bands.

We acquired many inexpensive

components from Lazarov Surplus Sales in Memphis, which sold parts

by the pound. Clint remembers clipping resistors out of some of

the equipment so we didn’t have to pay for the weight of the

unneeded chassis. Can you blame the workers for being annoyed with

us? Much of the war surplus electronics was designed for

24-volt military equipment, but we occasionally found 12-volt

amplifier vacuum tubes (1625s) and dynamotors which were the

standard way to produce the hundreds of volts needed to power the

AM vacuum tube transmitters that some hams put in their cars. We

each built 10-meter AM mobile transmitters for our parents' cars,

at a time when we were too young to drive. Clint still has an

operating version of one of those over 50 years later! The other

transmitter, unfortunately, went up in flames years later while

his mother was driving the car after Clint went off to college.

We acquired many inexpensive

components from Lazarov Surplus Sales in Memphis, which sold parts

by the pound. Clint remembers clipping resistors out of some of

the equipment so we didn’t have to pay for the weight of the

unneeded chassis. Can you blame the workers for being annoyed with

us? Much of the war surplus electronics was designed for

24-volt military equipment, but we occasionally found 12-volt

amplifier vacuum tubes (1625s) and dynamotors which were the

standard way to produce the hundreds of volts needed to power the

AM vacuum tube transmitters that some hams put in their cars. We

each built 10-meter AM mobile transmitters for our parents' cars,

at a time when we were too young to drive. Clint still has an

operating version of one of those over 50 years later! The other

transmitter, unfortunately, went up in flames years later while

his mother was driving the car after Clint went off to college.

CW came easy to us, probably because we started so

young. We both used mechanical bugs for sending code, and Clint

built an electronic keyer using vacuum tubes, but it never quite

worked right, sometimes running away and sending things never

intended. We got code proficiency certificates for 35 WPM, which

was the highest speed for which the ARRL tested. We were asked to

teach the code to adults who were studying for their General

license at the local Amateur Radio school. We would record code

practice sessions at 30 WPM on an old reel-to-reel tape recorder

and play it back at half speed for our students to practice so

that it didn’t take so long to prepare the lesson. To keep secrets

from our parents, we occasionally “spoke” to one another in Morse

code. Not exactly the same as the Navajo code talkers you’ve seen

in the movies, but you get the idea.

CW came easy to us, probably because we started so

young. We both used mechanical bugs for sending code, and Clint

built an electronic keyer using vacuum tubes, but it never quite

worked right, sometimes running away and sending things never

intended. We got code proficiency certificates for 35 WPM, which

was the highest speed for which the ARRL tested. We were asked to

teach the code to adults who were studying for their General

license at the local Amateur Radio school. We would record code

practice sessions at 30 WPM on an old reel-to-reel tape recorder

and play it back at half speed for our students to practice so

that it didn’t take so long to prepare the lesson. To keep secrets

from our parents, we occasionally “spoke” to one another in Morse

code. Not exactly the same as the Navajo code talkers you’ve seen

in the movies, but you get the idea.

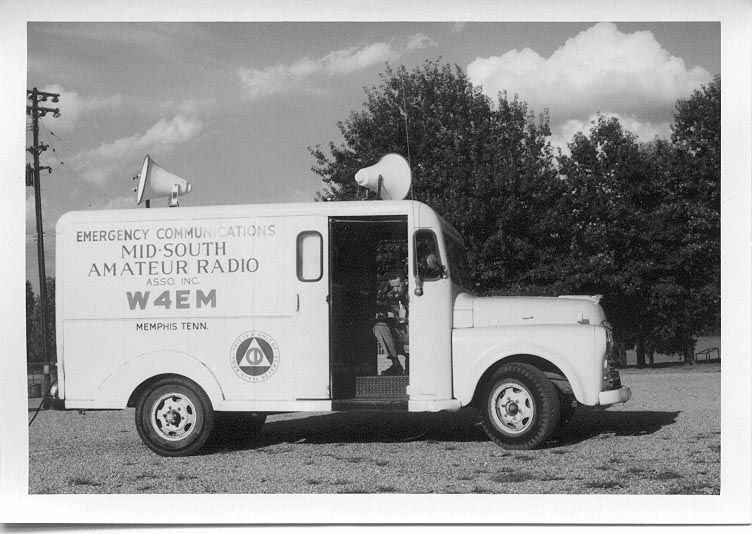

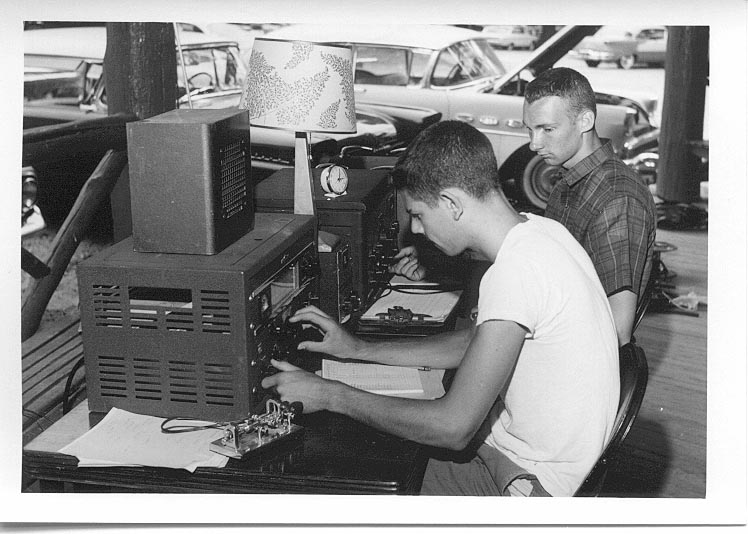

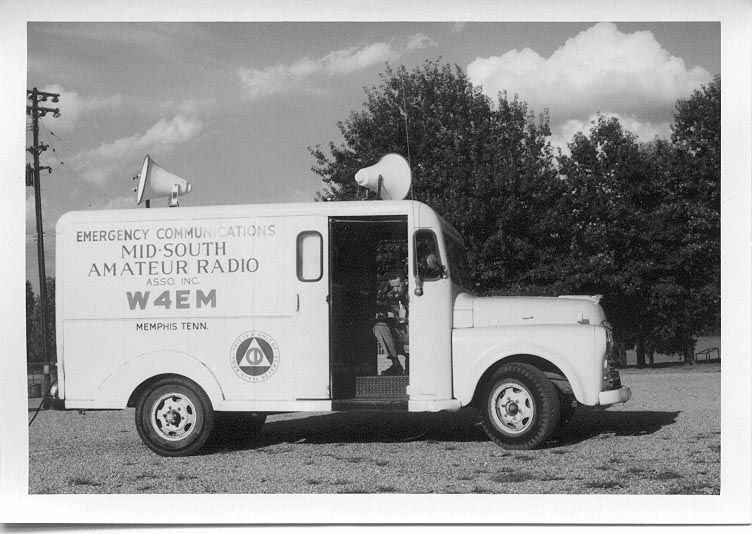

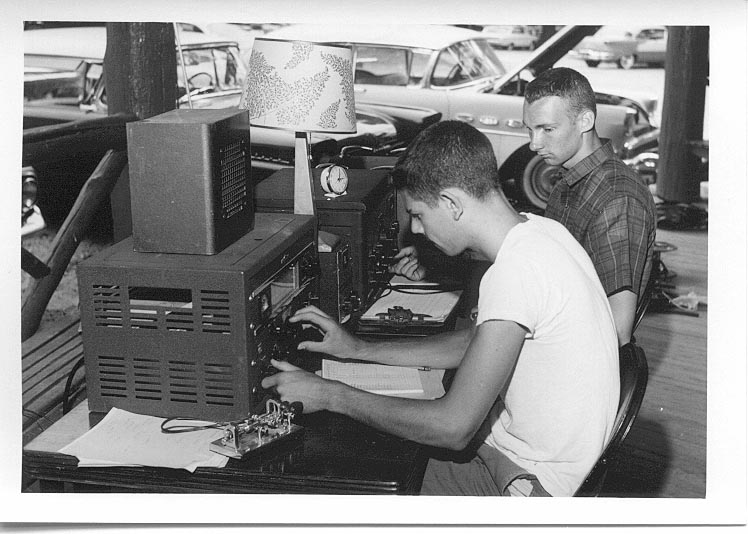

Field Day was always a summer highlight. We often operated W4EM,

the club station of the Mid-South

Amateur Radio Association (MARA) in Memphis. Quent is tuning

the Collins 75A-3 in this picture, and Clint’s hand is on the

Johnson Viking II transmitter. While still in high school, one

Field Day we set up our own station deep in the woods in Overton

Park and stayed up all night operating.

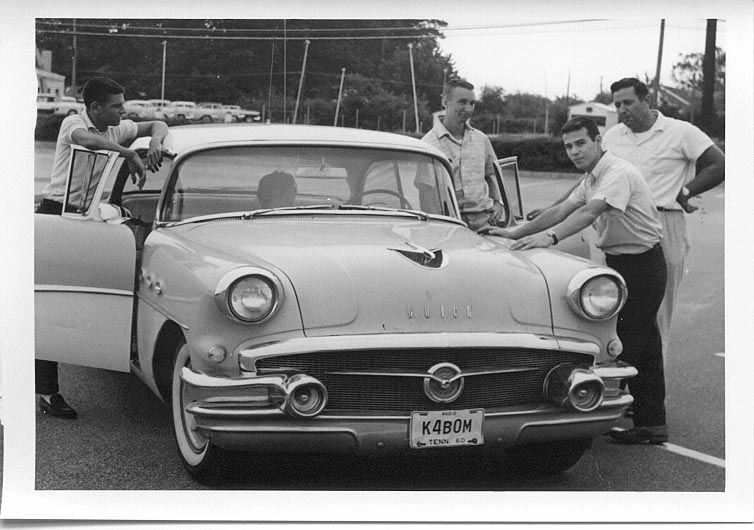

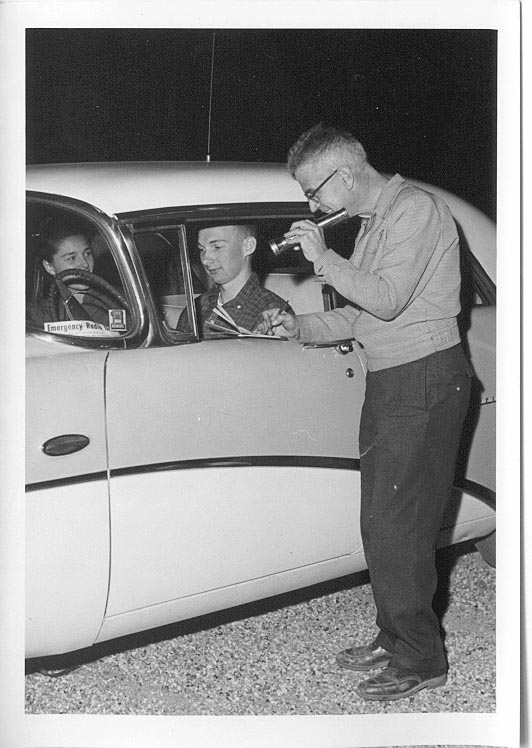

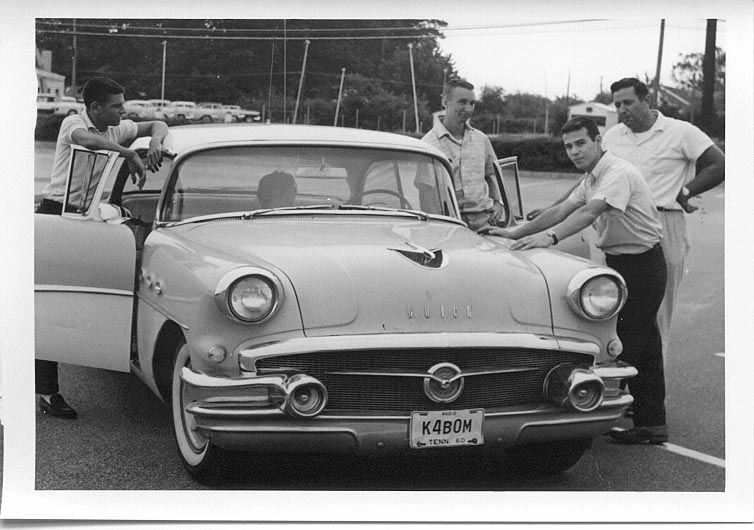

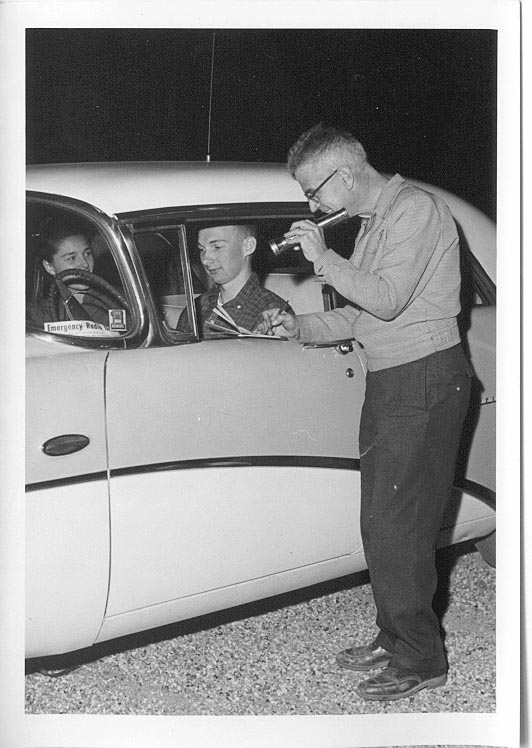

Biweekly transmitter hunts were very popular in

the late 50s in Memphis. This photo shows Quent (at right car

door) and Clint (at left car door) of Clint’s mother’s car before

the start of a rabbit hunt. Can you imagine what Clint’s mother

said after she found out that he had drilled a hole in the top of

her brand new 1956 Buick Special! Reluctantly she agreed that it

was better to plug the hole with a 2-meter antenna than just to

leave it. This photo shows Quent’s dad, Frank Cassen, W4WBK,

recording Clint’s mileage before the start of a hunt.

Although

transmitter hunts were conducted on 10 meters, the 2-meter antenna

was used for VHF communication using retired vacuum tube taxicab

radios that we converted to 2 meters. The receiver and transmitter

took up most of the trunk space. That was before the days of 2-meter

repeaters and commercial solid-state Amateur Radio transceivers.

Although

transmitter hunts were conducted on 10 meters, the 2-meter antenna

was used for VHF communication using retired vacuum tube taxicab

radios that we converted to 2 meters. The receiver and transmitter

took up most of the trunk space. That was before the days of 2-meter

repeaters and commercial solid-state Amateur Radio transceivers.

We used 29.627 MHz for the “Memphis 10 Meter Mobile Emergency Net.”

Everyone was crystal controlled since 7406.6 kHz quartz crystals

were easy to get from surplus outlets and VFOs weren’t so stable on

10 meters or even common on inexpensive and homebrew equipment. The

net met faithfully on Monday and Friday nights, although it seemed

no one ever had any traffic. Nevertheless, the operators and

equipment were well prepared for the many drills that they took part

in.

Once while at Clint’s parents’ lake home on Pickwick Lake in

northeast Mississippi, we decided to go on a DXpedition of sorts. We

overloaded Clint’s dad’s small boat with a gasoline-powered AC

generator, a large vacuum tube receiver (SX-100), an Eldico CW

transmitter, and a dipole antenna, and set up shop on a tiny island

in the Tennessee River, near the dividing line between Alabama and

Mississippi – all for the chance to sign K4BOM/4/5 on the air and

pretend we were DX. The pileups were feeble (nonexistent, really),

but it was our first time to be on the “wanted” end of a DXpedition

after working so many others. Miraculously, we got back to shore

without losing any equipment despite the very rough seas.

One might think that we always walked the straight and narrow, but

unfortunately “boys will be boys.” Quent had a receiver that could

tune to the local police and fire department, and Clint bought at a

police auction for $5 a vacuum tube receiver that was on a police

motorcycle that had been submerged for a month in the Mississippi

River and nursed it back to health. We would often converge on the

scene of local calls, first on bicycle and later by car after

getting our drivers licenses at age 16. Some of the police began to

know us. We would occasionally visit the police dispatcher and help

him dispatch cars. We once inquired about getting summer jobs as

police dispatchers but were told that one had to be 21 years old to

work for the police department, and so Quent took a summer job with

the electric company and Clint delivered packages for his dad’s

office supply company.

After high school we both went on to college. Clint became a physics

professor and Quent an electronics engineer. We have been involved

in a lot of interesting technical work in our careers. Without

doubt, our start in Amateur Radio with the Novice license opened

many doors and launched us into our interesting and rewarding

careers.

Quent Cassen and Clint Sprott

December 2006

We were surprised how easy it

was to work DX with very modest equipment. Ten-meter CW was really

hot. On the weekends we would get up early and work one European

station after another, staying with it all day until stations from

Australia and Japan would start to come in just before 10 meters

went dead in the evening. The world seemed a very big place to two

kids who hadn’t ventured very far from home. What we didn’t know

was that sunspot cycle 19, which peaked in 1957, still stands as

the all-time record. DX contests were a thrill for us. By 1959, we

both had our DXCC certificates and many other operating awards.

We were surprised how easy it

was to work DX with very modest equipment. Ten-meter CW was really

hot. On the weekends we would get up early and work one European

station after another, staying with it all day until stations from

Australia and Japan would start to come in just before 10 meters

went dead in the evening. The world seemed a very big place to two

kids who hadn’t ventured very far from home. What we didn’t know

was that sunspot cycle 19, which peaked in 1957, still stands as

the all-time record. DX contests were a thrill for us. By 1959, we

both had our DXCC certificates and many other operating awards. While still in high school we each

built our own Heathkit DX-100 transmitter. This photo is of Clint

in his basement shack, in front of his DX-100. We built many other

pieces of Heath equipment – receivers, transmitters, and test

equipment. Allied Radio in Chicago (via mail order) and the local

Amateur Radio emporiums in Memphis (Bluff City and W&W) soaked

up a lot of our allowances. We occasionally used the popular World

War II ARC-5 Command Set equipment that was readily available and

easily adapted for use on the Amateur Radio bands.

While still in high school we each

built our own Heathkit DX-100 transmitter. This photo is of Clint

in his basement shack, in front of his DX-100. We built many other

pieces of Heath equipment – receivers, transmitters, and test

equipment. Allied Radio in Chicago (via mail order) and the local

Amateur Radio emporiums in Memphis (Bluff City and W&W) soaked

up a lot of our allowances. We occasionally used the popular World

War II ARC-5 Command Set equipment that was readily available and

easily adapted for use on the Amateur Radio bands. CW came easy to us, probably because we started so

young. We both used mechanical bugs for sending code, and Clint

built an electronic keyer using vacuum tubes, but it never quite

worked right, sometimes running away and sending things never

intended. We got code proficiency certificates for 35 WPM, which

was the highest speed for which the ARRL tested. We were asked to

teach the code to adults who were studying for their General

license at the local Amateur Radio school. We would record code

practice sessions at 30 WPM on an old reel-to-reel tape recorder

and play it back at half speed for our students to practice so

that it didn’t take so long to prepare the lesson. To keep secrets

from our parents, we occasionally “spoke” to one another in Morse

code. Not exactly the same as the Navajo code talkers you’ve seen

in the movies, but you get the idea.

CW came easy to us, probably because we started so

young. We both used mechanical bugs for sending code, and Clint

built an electronic keyer using vacuum tubes, but it never quite

worked right, sometimes running away and sending things never

intended. We got code proficiency certificates for 35 WPM, which

was the highest speed for which the ARRL tested. We were asked to

teach the code to adults who were studying for their General

license at the local Amateur Radio school. We would record code

practice sessions at 30 WPM on an old reel-to-reel tape recorder

and play it back at half speed for our students to practice so

that it didn’t take so long to prepare the lesson. To keep secrets

from our parents, we occasionally “spoke” to one another in Morse

code. Not exactly the same as the Navajo code talkers you’ve seen

in the movies, but you get the idea.

Although

transmitter hunts were conducted on 10 meters, the 2-meter antenna

was used for VHF communication using retired vacuum tube taxicab

radios that we converted to 2 meters. The receiver and transmitter

took up most of the trunk space. That was before the days of 2-meter

repeaters and commercial solid-state Amateur Radio transceivers.

Although

transmitter hunts were conducted on 10 meters, the 2-meter antenna

was used for VHF communication using retired vacuum tube taxicab

radios that we converted to 2 meters. The receiver and transmitter

took up most of the trunk space. That was before the days of 2-meter

repeaters and commercial solid-state Amateur Radio transceivers.